Early Years of the Nazi Party

When the Nazi Party was born in 1919, the party platform presented the Judenfrage—the so-called "Jewish Question"—as a central issue Germans needed to face. Factually, Jews in Germany were a tiny minority, less than 1% of the population (around 525,000 people). They were highly assimilated and, in many cases, felt themselves more German than Jewish. Germany was their home.

In Nazi propaganda, these loyal citizens were portrayed as a source of genetic pollution. For the Nazis, the problem was not simply that Jews lived in Germany; they believed a broader racial problem existed. This view implied that, in their eyes, there was virtually no solution other than for Jews to leave Germany.

The Nazi Party remained marginal for quite some time. The 1923 coup against the state government in Bavaria famously failed, and Hitler, along with some of the other leaders, was imprisoned. This event is known worldwide by its German name, the Putsch. In the elections of May 1928, the party received only 2.62% of the vote.

Adolf Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany on January 30, 1933.

But Germany—then known as the Weimar Republic—suffered from economic instability, inflation, and unemployment. Some of the individuals involved in drafting the republic’s constitution were Jewish, a fact that fueled antisemitism as these societal problems deepened.

Following the 1929 Wall Street Crash, when the mentioned economic problems globalized, Hitler’s Nazi Party started to gain more votes. In July Federal Elections of 1932 Nazi party gained 37.3% of the vote becoming the largest party. Hitler was also a candidate in the Presidential Elections and although he was not elected, this candidacy established him as a more serious political player.

From its inception, the party was strongly connected with bitter rightwing WWI veterans. They formed a violent paramilitary group, the Freikorps. Hitler connected well with these men. In the streets the paramilitary SA (Sturmabteilung, Brownshirts) made sure that political opposition was abused and attacked.

Violence and threats of violence were a significant part of not just the Nazi path to power but the essential part of the regime and how people were governed.

Due to the volatile conditions in the society, well-meaning Conservative politicians promoted Hitler. They shared the mistaken belief that once he was in power, they could control him and eventually push him aside. It is no wonder then that President Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934) felt pressurized to appoint Hitler as the new Chancellor of Germany. This happened on January 30, 1933.

Early Policies

On February 27, 1933, the Reichstag—the German Parliament in Berlin—was set on fire. The reasons for the blaze remain somewhat uncertain to this day. A Dutch Communist, Marinus van der Lubbe (1909–1934), who was mentally disabled, was charged with the crime and executed by guillotine. Following the arson, the SS (Schutzstaffel), originally Hitler’s bodyguard, and the Gestapo, the political police, became increasingly involved in societal affairs.

The Head of Berlin Fire Department at the time was Walter Gempp (1878-1939). He spoke about his concerns regarding the origins of the fire. He was called to extinguish it late. He spoke about his concerns regarding the origins of the fire. Later, he was arrested and found murdered in prison.

Emergency legislation became effective the next day curbing freedom of expression, assembly, and press. (Some of the laws especially limiting the freedom of press had been effective from almost the first day of Hitler’s rising to power.) Citizens also lost some of their protection when accused of crime. They could for instance be arrested without specifying charges.

In March, Hitler was able to push through the Enabling Act, a law enabling measures used in a state of emergency. This was needed to quench opposition parties. Chief among those were the Communists. In practice the meaning of the Enabling Act was that parliament was no longer needed to enact legislation. Hitler with his willing cabinet would be able to do that. The burning of Reichstag contributed to this, as the incident created instability.

Atmosphere of Chaos

By 1933, there was a general atmosphere of chaos and fear in Germany, which the arson had only amplified. In this climate, the government wielded extensive powers: to arrest and detain people, to conduct searches without warrants, to listen to phone conversations, to read mail, and even to track down, beat, and kill citizens. Denunciations made it impossible to trust anyone; even children could inform their teachers about their parents. While some citizens fearfully withdrew from public life, others openly celebrated the changes.

What did it mean to be a citizen—or a bystander—under these changes? The renowned German writer Frank Thiess (1890–1977), himself a World War I veteran, famously spoke of Innere Emigration—“internal exile”—a stance whereby a person could disapprove of Nazism yet continue living in Germany. In such a life, the focus remained on family, friends, and everyday activities, while deliberately ignoring the troubling transformations taking place. This often meant turning a blind eye to worsening discrimination, street violence, or even incidents within schools.

In March 1933 anti-Jewish riots took place all over Germany. To the Jewish community, this was a shocking new development.

Jewish businesses...

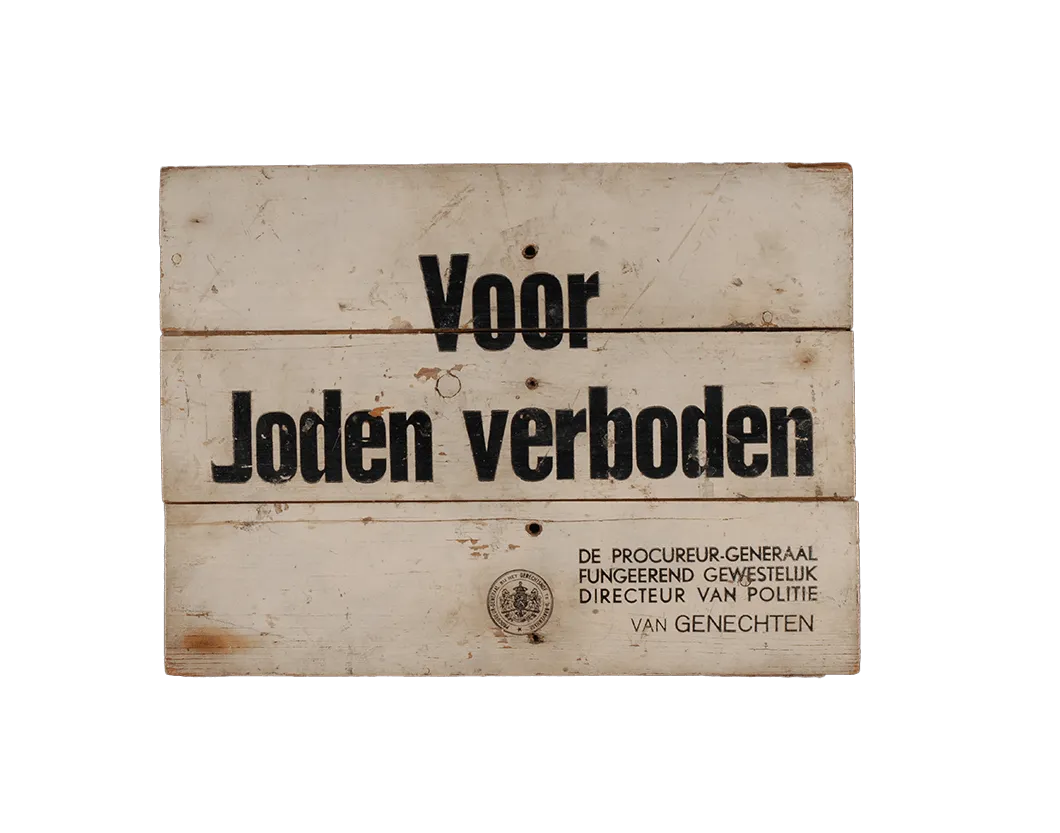

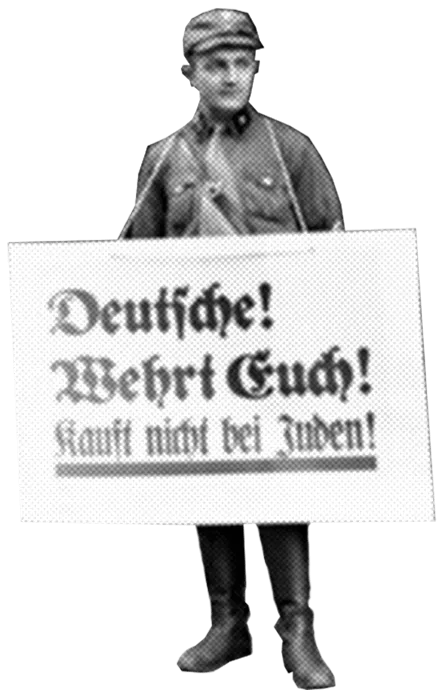

In April 1933 Jewish businesses were boycotted. Annoyed because other countries including the United States received news about what was happening to the Jews in Nazi Germany, this was a Nazi punitive action. The aim was that the Jews themselves would have to stop the “atrocity propaganda” going out to other countries.

Nazis wanted to show the world that whatever was happening to the Jews in Nazi Germany happened in the framework of law. In this context of the boycott, there was an order to not use violence but despite this there were attacks, and it damaged the Jews’ property.

For many Jews this was the end of their businesses. This was also a test case to see how far the regime could go. The attacks against Jewish businesses continued after April 1933 in different forms.

The first Racial Laws were enacted with Jews having to resign from Civil Service and as doctors from the Public Health system.

In May 1933 book burnings took place all over Germany. The books themselves were of Jewish origin or of a pacifist or democratic nature.

By June 1933, 27 000 people, among them Communists, Socialists and Trade Union Leaders, had been arrested as threats to the regime. Germany became a one-party dictatorship. The meaning of this to the citizens was an increasing atmosphere of terror.

The Concentration Camp of Dachau was opened in March 1933 as the first official concentration camp established by the regime. At that point it was a place to incarcerate potential and real opponents of the Nazi regime. Later, the camp system expanded to include different types of camps. The number of Jewish prisoners increased as persecution of Jews became harsher. Dachau’s commandant Theodor Eicke (1892-1943) soon established a brutal prison regime. Prisoners had to work in harsh conditions.

Thousands of executions took place and about 2500 prisoners were taken to Hartheim, a euthanasia center where they were murdered by gas. Medical experiments and specific experiments for the air force, Luftwaffe, by were performed by scientists on defenseless prisoners. Dachau became a training ground for the SS and a model for other camps. Throughout its existence Dachau housed about 200 000 inmates.

Nuremberg Race Laws in 1935 officially made the Third Reich a Racial State depriving Jews of their German citizenship and restricting marriages. The goal was to separate and segregate Jews from the population. The Laws are called by the name of the city where they were first announced. This was on September 15, 1935.

One aspect of the law was the Reich Citizenship Law depriving the German Jews of their German citizenship. Citizenship was now based on ‘German Blood’. The other aspect was the Law for Protection of German Blood and German Honor. This was a law against ‘race defilement’ including making intermarriages illegal. The Laws had under-sections and many practical implications. German Jews now lost their rights as citizens. This was a very grave situation.

By 1938, Nazi Germany had undergone a profound transition. It was now a one-party state that controlled nearly every aspect of its citizens’ daily lives.

In March 1938, Nazi Germany carried out the annexation of Austria, known as the Anschluss. The term is fitting, as many Austrians welcomed the act. Large numbers eagerly delivered Jews to the Nazis and publicly humiliated them in the streets.

The outside world was powerless, consequently, in September 1938 in Munich the Western Powers allowed Germany to annex the Sudetenland in Western Czechoslovakia. Sudetenland where a big German population was living, was one of the areas Germany had lost because of the peace treaty ending WWI.

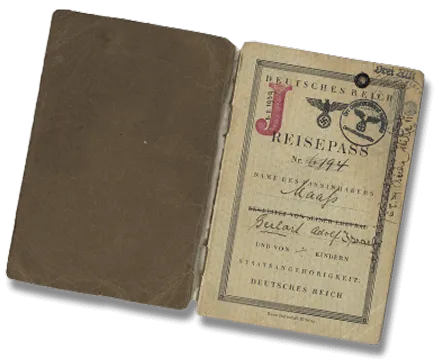

In relation to the Jews, a decree was created on August 1938 that all Jews must carry an ID card with themselves all the time so they would be recognized. This decree became effective from January 1939. In addition, Jews bearing names that could be confused with non-Jewish names had to add ‘Israel’ and women ‘Sara’ to their name in the ID cards.

All Jews’ passports were invalidated from October 5th, 1938, unless they were marked with a letter “J” (to make emigration more difficult). It is noteworthy that earlier Swiss government officials had discussed this course of action with their German counterparts.

Paul Grüninger (1891-1972) was a Swiss border police commander in the area of St. Gallen.

The outside world remained largely powerless. Consequently, in September 1938, during the Munich Agreement, the Western Powers allowed Germany to annex territory.

Soon after, as a result of negotiations between Switzerland and Nazi Germany, Jewish passports were stamped with the letter “J,” making it increasingly difficult for Jews to enter Switzerland.

As conditions in Nazi Germany worsened, more and more Jews tried to escape to Switzerland. Grüninger decided to act against his country’s policy.

He even stamped the refugees’ passports with a March 1938 date, thus making them eligible to enter the country.

As the Germans informed Swiss authorities about his actions, he was dismissed from his position and ostracized by the community. He lived a very hard life.

Yad Vashem recognized him as Righteous Among the Nations in 1971.

Alongside legislation, the Nazis understood well the power of propaganda. The Nazi Party was consistently portrayed as the only party that “all Germans could support.” All Aryan German citizens were invited to join a greater movement. Belonging to the party was presented as more than membership in an ordinary organization; it was portrayed as a higher purpose in life. The chief instrument for promoting the Nazi Party was the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, led by Joseph Goebbels (1897–1945), a master of deception.

Joseph Goebbels (1897-1945) had a doctorate from Heidelberg university (1921). He is generally considered a genius of propaganda. Goebbels like many of Hitler’s trusted advisors, was with Adolf Hitler from early on. His role as the Minister of Propaganda was crucial in getting the German public to support Hitler and Nazi policies. He was a skillful speaker. He was also one of Hitler’s appointed successors. His devotion to Hitler was such that he and his wife Magda murdered their children and then committed suicide in Hitler’s bunker in Berlin. Soviet troops were already closing in. This was in April 1945.

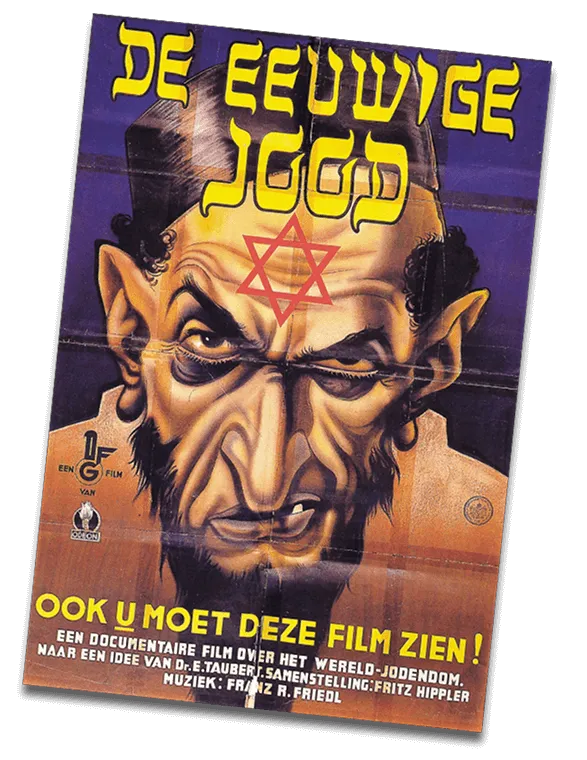

Nazi newspapers, such as the Völkischer Beobachter, (People’s Observer) were established early on to propagate for the Nazis. Racial propaganda was spread in this manner from early on. All art, films, music, and theater had to serve the greater goals of the party. So-called degenerate art, including all expressions of modern art, claimed to be un-German was banned.

One of the main aims of the propaganda effort was to show the Jews as the enemy. This would raise tolerance of violent actions against the Jews. In the propaganda Communism was linked to Jews, which justified Germany’s 1941 attack on the Soviet Union and the ensuing mass murder of the Jews in the area.

It is noteworthy that much propaganda was geared toward the Allies seeking to justify Germany’s aggression in various parts of Europe.

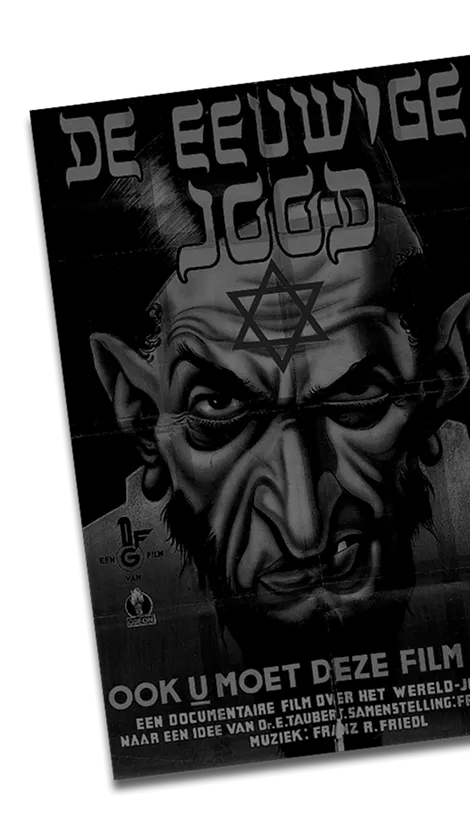

One of the most important Nazi films was Fritz Hippler’s (1909-2002) ‘The Eternal Jew’ of 1940, which accused the Jews of being societal parasites. On the other side of propaganda, the famed film-maker Leni Riefenstahl (1902-20039) used her talents to praise Hitler and his party in the ‘Triumph of the Will’ of 1935.

Later during WWII, propaganda was used to cover up terrible atrocities committed in the Eastern Front and against the Jews. As German public entered movie theaters, they were always shown propaganda films before, during, and after the films they came to watch

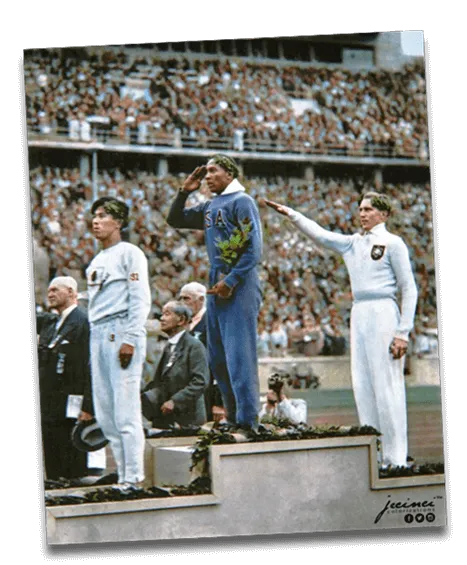

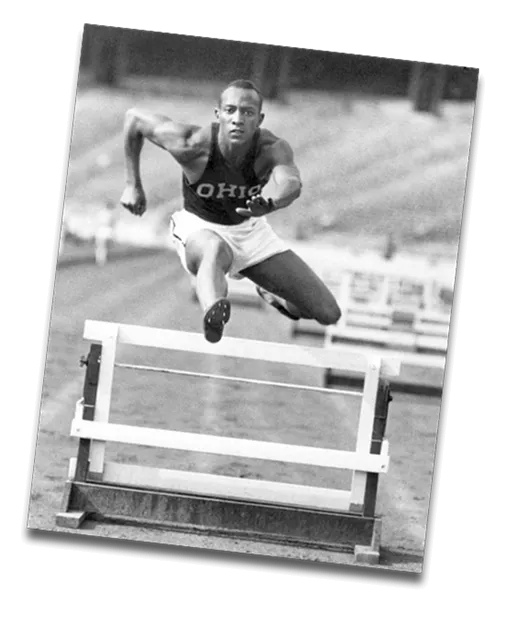

In 1936 Nazi Germany hosted the Olympic Games in Berlin. It is very important to know that for the first time in history an attempt was made by citizens from the United States and several European nations to boycott Nazi games. As this attempt was unsuccessful, the hosting of the Olympic Games was a great Nazi propaganda victory. Berlin was cleaned of troubling racial propaganda and Germany’s already existing growing mood for expansion was hidden too – everything appeared normal.

What is interesting is that in the atmosphere of racial propaganda, an African American athlete Jesse Owens (1913-1980) won four gold medals. In Germany, most Jewish athletes were already expelled from sports; now one female fencer Helene Mayer (1910-1953) was allowed to compete. There were also Jewish athletes from other nations who competed. Nine Jews won medals in these games.

In the troubling atmosphere of later 1930’s, the world already recognized a danger in Hitler. In 1938 Adolf Hitler’s face was on the front page of the famed TIME Magazine. Hitler was chosen as TIME Magazine’s Man of the Year. This was as far as he’s known to us not because of agreement with his policies. Rather it was recognition of his growing role in Germany and the world.

Adolf Hitler understood that training German youth into the Nazi culture was a way to secure the future. One way of doing this was to ban other youth movements and obligate German boys to join the Hitler Youth.

In this manner young people were separated from the influence of their parents or churches, they were vulnerable. There were different levels according to ages so that children as young as 10-14 would be part of a group for younger boys whereas boys from age 14 to 18 were part of the regular Hitler Jugend (Hitler Youth).

Camping, hiking, and other fun outdoor activities were included alongside military training and party propaganda.

Clearly, the goal was to indoctrinate and prepare soldiers for the German Army. Youngsters had to swear an oath to Adolf Hitler as well as the Nazi flag considered a blood oath.

It is estimated that by 1939, just before the outbreak of WWII, 90% of German Youth belonged to Hitler Youth or equivalent girls’ groups.

Refusal to join was a costly option. Discipline inside the movement was severe. At the later stages of the war, when Germany was clearly losing the battle, even young boys were sent to the front.

Schools in Nazi Germany were regulated by politics. There was a Nazi Teachers’ Union and by 1937 almost 100% of teachers were members. The teachers had to present proof of their own Aryan ancestry. They had to teach racial theories and antisemitic ideas including bending history to suit the Nazi narrative. Jewish children have described their experiences; there was an increasing sense of isolation at school, interestingly testimonies seem’ to show that teachers were harassing them more than other children.

Camping, hiking, and other fun outdoor activities were included alongside military training and party propaganda.

Clearly, the goal was to indoctrinate and prepare soldiers for the German Army. Youngsters had to swear an oath to Adolf Hitler as well as the Nazi flag considered a blood oath.

It is estimated that by 1939, just before the outbreak of WWII, 90% of German Youth belonged to Hitler Youth or equivalent girls’ groups.

Refusal to join was a costly option. Discipline inside the movement was severe. At the later stages of the war, when Germany was clearly losing the battle, even young boys were sent to the front.

During the Holocaust, when things were extremely difficult, there were teachers in Europe who showed great understanding towards the plight of Jewish pupils.

Andrée Geulen (1921-2022) from Belgium was only twenty years old when as a young teacher she saw the yellow stars on her Jewish students’ clothes. She acted immediately by having every child were an apron, so the star was hidden. She then became involved with the rescue of Jewish children upon meeting a member of an illegal organization.

Yad Vashem recognized Andrée Geulen as a Righteous Among the Nations in 1989.

During a Nazi raid of another school, she showed courage and determination. Under a false name, the young woman escorted children to hiding places whether in families,

monasteries, or convents.

With a Jewish partner Ida Sterno, she visited the children and kept their identities committed to her memory – for the time after war. When Ida Sterno was arrested, Geulen had to go underground. Following the liberation, she looked for the children’s families and kept in contact with them.

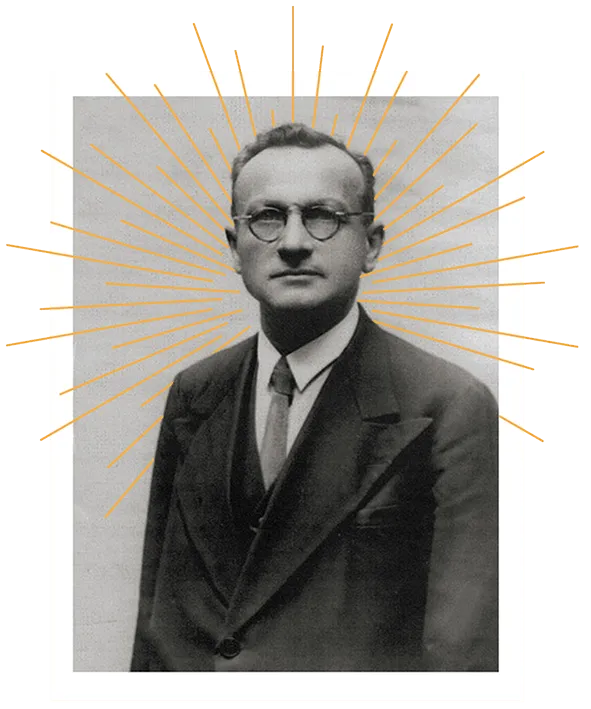

Joseph Migneret (1888-1949) was a French public elementary school principal in Paris. His school was located in the Marais district, where a sizeable Jewish population was living.

In 1942 Germans started deportations and he saw many French Jews, among them his current and former students, being taken away. Seeing their desperate conditions, he decided to help. He joined the resistance. Not only did he provide them false documents, but he even hid students in his own home.

Yad Vashem recognized Joseph Migneret as Righteous Among the Nations in 1990.

In the 1930s, c. 60% of Germans were Protestants and c. 40% were Catholics. In addition, there were some smaller denominations in Germany. Whereas the Catholic Church was one, Protestants were divided.

Much of the German Protestant Church supported National Socialism even calling themselves Deutsche Christen. It could be argued that the meaning of this was that they were first Germans, then Christians.

As propaganda effort was advancing, the Nazi Party tried to unite all Protestants under Deutsche Christen and its leader Ludwig Mueller (1883-1945) whom Hitler appointed as Reich Bishop.

Instead of looking at things from a Biblical and theological point of view, Mueller brought Nazi racial ideology into the church. He wanted purge Jewish influences even from the Bible.

On the Catholic side, local opposition was stymied by the Vatican’s Concordat Agreement directly with Adolf Hitler in 1933.

The Bekennende Kirche (Confessing Church) was created as a theological opposition. Its leaders generally believed that anyone baptized was a Christian. This applied to those of Jewish origins. These pastors had no desire to change the Bible.

It is important to note though that their opposition to the Nazis was largely on account of the control Nazis wanted to exercise over the church and not so much because of racial policies.

Perhaps the best-known leader of the Confessing Church is Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945). From an aristocratic family background, he made the startling choice of studying to become a Lutheran pastor.

In 1933 he was too afraid to attend a Jewish funeral. Later on, he regretted this and started speaking out. He warned that the Führer (leader) could turn out to be the Verführer (seducer). Despite being offered opportunities to stay apart during WWII, he decided that he had to be in Germany with his people.

In practice one could be both a member of the Confessing Church and of Nazi Party. Another famous Confessing Church founder, pastor Martin Niemöller (1892-1984) refused to sign an oath of loyalty to Hitler and spent war years in concentration camps.

After the war he confessed to having been an anti-Semite when it all began. It is said that until the very end of his life there was a contradiction inside him about his national German identity and what had happened during WWII and the Holocaust.

He wrote an often-cited poem about the developments in Nazi Germany: “First they came for the Socialists and I did not speak out because I was not a Socialist.Then they came for the Trade Unionists and I did not speak out because I was not a Trade unionist.Then they came for the Jews and I did not speak out because I was not a Jew.Then they came for me and there was no one left to speak for me.”

One of the most significant pre-Holocaust events was Kristallnacht—also known as the Novemberpogrom (November Pogrom)—which took place on November 9–10, 1938.

Just days earlier, on October 28, some 17,000 Polish Jews living in Germany were arrested and deported to a no-man’s land between Germany and Poland. Abandoned by both countries, they endured horrific conditions.

Word got to a young Jewish man, Herschel Grynzspan (1921-1944) in Paris that his family were among these unfortunate ones. He entered the German Embassy in Paris and, in the absence of the Ambassador, shot the Third Secretary Ernst Vom Rath (1909-1938) who died on November 9.

Nazi party leaders were gathered in Bavaria at the time. The date commemorated the failed Putsch of 1923. Their instructions were now sent all over Germany. The shooting became an excuse to horrific attacks against Jews, their businesses, and synagogues all over Germany and Austria during November 9-10, 1938. (Austria at that point was part of the Reich, that is Nazi Germany.)

Nazi party leaders were gathered in Bavaria at the time. The date commemorated the failed Putsch of 1923. Their instructions were now sent all over Germany. The shooting became an excuse to horrific attacks against Jews, their businesses, and synagogues all over Germany and Austria during November 9-10, 1938. (Austria at that point was part of the Reich, that is Nazi Germany.)

A, SS. Hitler Youth and private citizens were all participants. To summarize, on the Night of Broken Glass (November 9-10, 1938), Jews were targeted in state-instigated acts of public vandalism, arson, and violence in Germany and Austria. That night, 267 synagogues were burned, 1,400 were damaged, and over 7,000 Jewish businesses were vandalized. Graveyards were attacked too.

This action resulted in financial ruin

About 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps. Suddenly, tens of thousands of Jews realized they needed to leave Germany.

Was this open display of anti-Jewish violence the beginning of the end?

At any rate, on November 12, an important meeting by the Nazi leaders took place – forced immigration was no longer the option. Other far more sinister things were to come. Within days and weeks following the Kristallnacht, several new anti-Jewish decrees were enacted severely restricting Jewish life in Germany.

Regarding economic damage, it was great. Jews themselves had to pay for all the damages so in some ways this was the beginning of their economic ruin in Nazi Germany. Over 100 000 Jews left Nazi Germany in the months following the event.

They left for other European countries, the United States, Palestine Mandate and Shanghai, China.

Heinrich Himmler (1900-1945) came from a middle-class Catholic family. Following his army service, he worked as a salesman and a chicken farmer. During the time he became increasingly connected with the Nazi party.

In 1923, Himmler was involved with Hitler’s unsuccessful coup attempt against the Bavarian government.

As one of Hitler’s chief advisors, Himmler was intimately connected with every aspect of the Holocaust. In 1933, he established the concentration camp of Dachau.

As he became exceedingly powerful and feared, he was made the leader of the SS and the entire German Police. In 1938 Himmler was one of the main organizers of Kristallnacht.

Ruth Steinfeld was 5 years old at the time of Kristallnacht. On the HRA18 website you can read more about her story.

“That night, while we were eating dinner, two Nazi soldiers with knee-high black boots knocked down our front door with hammers and axes. They broke everything in the house.

All of our possessions were destroyed, broken glass was everywhere, and everything we owned was broken to pieces. Then, the soldiers took my father away.” Later, Ruth and her family were loaded into box cars like animals for four days and three nights. On the train to Camp de Gurs in France, “women were constantly screaming and crying.”

After five months in the camp, Ruth’s mother was desperate for her daughters to have a chance to live. She selflessly “placed her children in the arms of strangers” by giving Ruth and her sister up to be rescued by the Children’s Aid Society (OSE) in France.

“My mother let go of her children, forced us to leave, so she could save our lives – knowing she was facing a death sentence, but hoping if she surrendered us to the care of others, our lives would somehow be spared. Her bravery, love, intuition, and clarity of mind amaze me to this day.”

Larry Steinfeld, later Ruth’s husband, was born in Hameln, Germany, in 1930 as the only child of Frieda and Morris Steinfeld. In 1938, he and his family arrived in New York, escaping Nazi Germany. His formative years were spent in Washington Park, in the Bronx. Although he retained fluent German throughout his life, Larry adopted a native New York accent. He attended City College in New York before serving in the Korean War as a German translator.

Larry moved to Houston in 1953 and continued his studies at the University of Houston. He found his talent in sales, first by selling shoes and then cars which he sold for 45 years. His lucky break happened in 1953 when he went to Houston’s Jewish Community Center and met a young, beautiful German Jewish immigrant, Ruth Krell. She had survived the Holocaust as a Hidden Child in France, but lost all of her family in the war except for one sister, Lea.

Larry and Ruth quickly fell in love and were married in 1954. They started a family with the birth of a daughter Susie, followed by another daughter Fredda and then a third daughter Michelle. Larry stayed active by running around Memorial Park on many Sunday morning. He enjoyed the household of his wife, three daughters, their many high school and college sorority sister friends and several phone lines ringing day and night. Larry was very comfortable with women and was able to charm them with his “baby blues” throughout his life.

In his later years, Larry shared his extensive knowledge of World War II and the Holocaust as a docent at the Holocaust Museum Houston. He also discovered a second career—and a true passion—as a substitute teacher in private schools. Beloved by his students, “Mr. Steinfeld” became known not only for his engaging presence but also for the pretzels he always brought as classroom snacks. Beyond teaching, Larry expressed his creativity through cartoon drawings, witty jokes, and the clever poetry he wrote for special occasions.

Could ordinary German citizens have changed the course of history? The evidence suggests otherwise. When synagogues burned, there is little record of public protest or widespread outrage. As far as is known, only one pastor in Berlin dared to speak out, lamenting openly the destruction of God’s houses.

For instance, Pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer had believed in pacifism but was forced to change his opinions, as events unfolded to a more violent and brutal direction. One of his sisters married a Jew – later Bonhoeffer helped to get them both out of imminent danger in Germany.

In his notebook pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer referred to Psalm 74:8 “…they burned all the meeting places of God in the land…” writing the date of the Kristallnacht next to it.

What is clear is that the world opinion did turn against the Nazi regime as people around the world saw reports about the Kristallnacht. There were demonstrations. There were outraged newspaper articles. But we need to consider that for instance in America there was widespread antisemitism.

This too needed to be weighed up by politicians. It could be concluded that despite the outrage many people truly felt there was not so much practical change in policies.

Clearly, Nazi Germany wanted its territory judenfrei (free of Jews) and judenrein (cleansed of Jews).

It is worthwhile considering the response to Nazi Germany’s actions by the outside world. Where could Jews have gone in the 1930s?

In July 1938, an international conference took place in the resort of Ėvian, France to discuss this very issue. The conference was initiated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, (1882-1945) due to mounting public pressure. Yet, Americans at that time were reluctant to receive Jewish refugees. This is clearly evidenced by, for instance, newsreels shown at cinemas at the time.

Antisemitic attitudes were reportedly common at the State Department. Low-level delegations were sent to Ėvian by most nations. This ensured that no decisions to admit too many refugees would be committed to; even the US representative made excuses. Here thirty-two nations refused entry. The Dominican Republic, despite its extreme poverty, promised visas to thousands, even 100 000, refugees.

Despite the politically motivated decision by the dictator Generalissimo Rafael Trujillo (1891-1961), this meant life rather than death to some Jews. Ultimately less than 1000 refugees made their way to the Dominican Republic. At the time the other option they had was Shanghai, which did not require visas to enter. Around 20,000 Jewish refugees entered here.

In Nazi Germany, it was reported to Reinhard Heydrich, (1904-1942), then in a high position related to security, that emigration of Jews from Germany would no longer be an option. It was even reported to him that Jews were abhorred by some countries. This goes to show how closely Nazi Leadership was watching the reactions of the world.

Chaim Weizmann (1874-1952), who later became the first President of the State of Israel, said:

It is worth remembering that a British Member of the Parliament and later Prime Minister Winston Churchill (1874-1965) did recognize the danger Hitler posed as well as the dangers inherit in the Munich Agreement. Churchill made a speech to that effect upon Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s (1869-1940) return from the Peace Conference in 1938.

Sudetenland had been handed over to Hitler in the Munich Peace Agreement and Jews were mow fleeing from the area. In addition, there were the Jews fleeing from Germany and Austria.

Following the Kristallnacht and an appeal from the British Jewish Refugee Committee, the British Parliament authorized a special Kinderstransport (Children’s Transport Program) whereby 10 000 children under the age of seventeen mainly from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Poland were relocated to the United Kingdom.

They were forced to leave their families behind, carrying only a small bag, and set out with other children toward an unknown country and an uncertain future. Many people took part in this remarkable rescue effort. Among them was a young stockbroker, Nicholas Winton (1909–2015)—later knighted as Sir Nicholas Winton—who visited Czechoslovakia at the invitation of a friend. There, he witnessed anti-Jewish demonstrations in the streets and the poverty and misery endured by the 250,000 Jewish refugees.

He started battling bureaucracy in London on behalf of Czechoslovakia’s Jewish children. Winton gained permission to bring children to the UK provided that foster families and financial guarantees were found; after all the children arrived in Britain with only a suitcase. Little did they know that they would never see their parents again.

It is estimated that more than 6,000 people alive today owe their existence to Winton’s actions. Yet his story remained largely unknown until 1988, when a BBC television program reunited him with some of the children he had rescued and brought his extraordinary efforts to the attention of the world.

During June 1939, a German liner, a refugee ship St. Louis, carrying over 900 Jewish refugees, was sailing to Havana, Cuba with a permit to embark. During the voyage, a military coup had taken place and entry was promptly refused.

Despite desperate cables, the ship was refused entry to Canada and the United States as well. Antisemitism, including a Nazi movement were growing in the USA at the time. There was much reluctance to admit refugees.

St. Louis had to return to Germany; most of the passengers perished in the Holocaust. In this instance, entire nations became silent bystanders. Indifference ensured that brave souls who escaped were nevertheless forced to go back. This could not escape the notice of the Nazi leadership. No one wanted the Jews.

Survivor and Author Primo Levi said:

“Monsters exist, but they are too few in number to be truly dangerous. More dangerous are the common men…ready to believe and to act without asking questions.”

Truth vs. Lie What does it mean to tell the truth? Something is true when it reflects facts or what’s real. Tell a story about a time you told the truth.What is a lie? A lie is when you know the truth and tell a different story. Tell a story about a time you told a lie.

Small Talk – Telling the Truth

Brave – Sara Bareillis

Happy – Pharrell Williams

Count on Me – Bruno Mars

How can you be brave? How can you bring happiness to yourself and others? Share a time when someone was able to count on you.

Class discussion: What is the difference between a truth and a lie? Can you tell when someone is lying? How? Share about a time when you told a lie. What happened? Let’s play a game called Two Truths and a Lie. Form a circle as a class or in small groups. One child starts by telling the group two truths and one lie about himself/herself. Try to use a straight face so that all three could be believable truths. The other children try to guess which was the lie by a show of hands. After playing the game, discuss: Was it easy to tell the difference between a truth and a lie? Why or why not? Why do you think people in Nazi Germany believed lies about Jews?

Teacher clicks the link to bring up the photo. Take a close look at the families on board. What do you see see? (ex. Children, smiles, love, hope for rescue) Why did Cuba and the United States refuse to give permission and accept the passengers? The ship had no choice but to return to Germany. What happened to hundreds of those passengers? The world’s silence convinced the Nazis that no one cared about the Jews. With a partner, talk about ways your can care about others, especially those who look or act different from you. Why is it important to care?

Discuss with a partner: What stays with you after viewing the video? What groups in school are the most popular? Why? Who is left out or ignored? Are some students bullied? How do you think that feels? How can you stand with fellow students and make friends with a variety of people? Why does this for the future of the world?